Every textbook on number theory will begin with a treatise on prime numbers; every treatise on prime numbers will begin by emphasising their importance as building blocks or atoms of our number system: every integer can be expressed as a product of prime numbers in one way and one way only. Six is two times three and there is no other way to decompose it.1 Euclid proved this over two thousand years ago and it is so fundamental (hence the name fundamental theorem of arithmetic) to our thinking about numbers that we take it for granted. It is not!

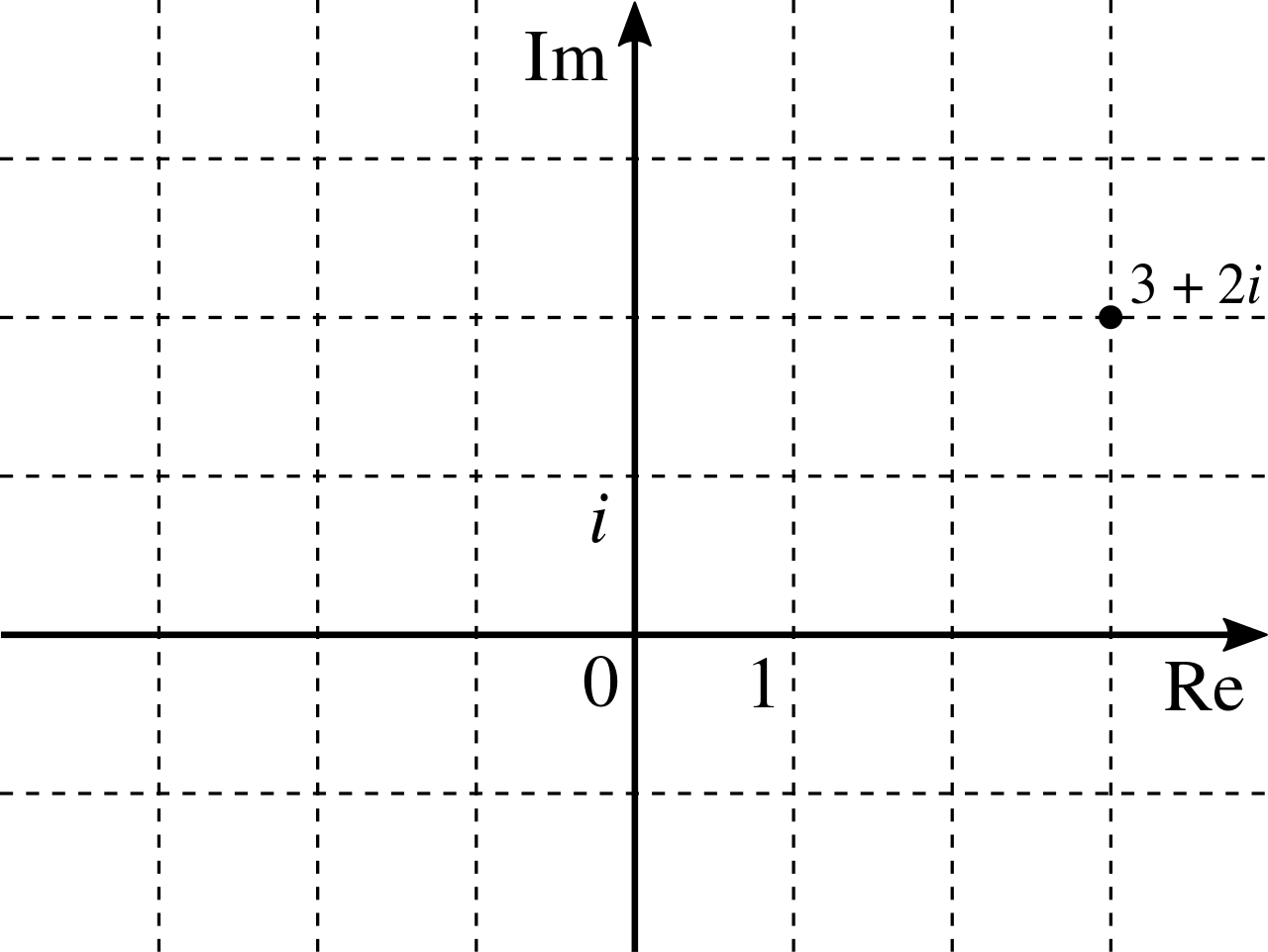

There are numbers that behave very much like the integers but have a different structure. One rather simple example are the Gaussian integers (usually denoted \(\mathbb Z[i]\)) which look just like complex numbers \(z=x+iy\), except that \(x\) and \(y\) are restricted to integer values. They live in the complex plane, but exclusively on a discrete grid amongst their continuous cousins.

Every ordinary integer is also a Gaussian integer (think \(x+0i\)); other examples include \(i\), \(- i\), \(1+i\), \(1-i\), etc. Just as with the integers we can start decomposing numbers as products and develop a notion of primality. Our first important observation is that \(2\) is no longer prime! It decompose to \(2=(1+i)(1-i)\). On the other hand, \(3\) is still prime as a Gaussian integer. But as it turns out, other than losing a few primes and gaining a few new ones, the Gaussian numbers are still very well behaved and have most of the properties the integers have, including unique prime factorisation. The primes in \(\mathbb Z[i]\) make pretty pictures:

Things change when we consider a different set of numbers which we’ll denote \(\mathbb Z[\sqrt{-5}]\). They are of the form \(z=x+y\sqrt5i\) and have a surprise in store: Looking at the decomposition of \(6\), we can of course still do \(6=2\cdot3\), but we also have \(6=(1+\sqrt5i)(1-\sqrt5i)\). Maybe this does not surprise you – after all we’ve already seen that some of our beloved primes decompose in some other systems such as \(2\) does in the Gaussian integers. The difference here is that neither \(2\) nor \(3\) decompose in\(\mathbb Z[\sqrt{-5}]\) – we have found a truly different decomposition! This proves that our new set of numbers does not have a unique prime factorisation.

What I’ve given you is a small taster of algebraic number theory. It’s the regular follow up course to the introduction or elementary course and will teach you that much of the regular behaviour of the integers can be restored if you move from considering numbers to ideals. But that’s way beyond the scope of this article.

Now, you may find all these “new” numbers esoteric if not abstract nonsense. But they do have broad applications – within mathematics, of course. In fact, these rings or domains we call \(\mathbb Z[\sqrt{d}]\) first emerged in the study of Fermat’s Last Theorem at the end of the 19th century. After a prize has been announced for its solution by the French Academy of Science the highly reputed mathematic Gabriel Lamé announced a proof within a year. His approach used the kind of numbers I introduced here, but was destroyed by Ernst Kummer when he pointed out that the proof implicitly relied on the unique factorisation property they don’t necessarily have. Lamé’s assaults were cancelled2 and it would take another century before Andrew Wiles would take algebraic number theory to a completely new level. But that is way beyond the scope of this post.3

-

Yes, you can write \(12\) as \(3\cdot4\) or \(2\cdot6\), but you can continue either way and eventually reach the unambiguous \(2\cdot2\cdot3\). ↩︎

-

Which is not to say the work was in vain: Kummer developed said ideal theory and used it to prove a large (in fact, infinite) number of cases of Fermat’s Last Theorem. The study of our new number friends developed in the meantime their own ever more abstract life which has little to do with number theory and is in my humble opinion nothing but tedious and boring. ↩︎

-

If you are interested in the whole story, there’s no better (popular) source than Simon Singh’s book. ↩︎