After all this playing with the \(\zeta\)-function it is time to return to the overall objective of this whole exercise: counting prime numbers. The idea behind analytic number theory is that primes are unpredictable on the small scale, but actually surprising regular on the large scale. This is why we’ll look at certain functions that behave pretty erratically when we look at every single value, but become smooth and “easy” to calculate once we “zoom out” and consider the global properties, the so-called asymptotic.

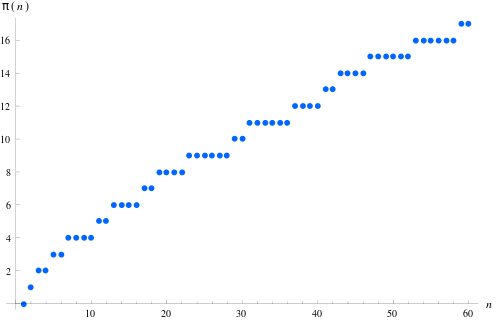

I’ve mentioned the function \(\pi(x)\) before which is defined as the number of primes not exceeding some real \(x\). (Never mind the overloading of the symbol \(\pi\) for different and completely unrelated functions, constants, etc. It’s been like that for ever, and always will be. Mathematicians are pretty stubborn.) If we can calculate \(\pi(x)\) exactly, we would have perfect information about the primes since the function counts the primes exactly. Theoretically. But as mentioned before, we are only interested in capturing the overall behaviour, forgetting “local” irregularities.

So, what does \(\pi(x)\) look like? Most of the time, it is just a flat line for most of the values when the count does not change as they are not primes. At every prime value it jumps up by one step. That’s it.

Well, almost. It turns out that it’s convenient to define the value of \(\pi(x)\) for primes as “half the step”, i.e., the value of \(\pi(4.9)\) would be \(2\), \(\pi(5)\) is \(2.5\), and \(\pi(5.1)\) then takes the value \(3\). It doesn’t matter asymptotically, but the arguments that follow will go more smoothly. Yet, this is quite inconvenient to write out every time, so I will drop it for most of time, but always implicitly assume that functions at values where the argument jumps are “smoothed out”.

It is usually interesting to look at the density of a certain sequence, i.e., the proportion of all integers that are members of that sequence. In this case it means calculating \(\pi(x)/x\). But already quite elementary arguments are sufficient to show that this value tends to zero. In other word, the density of the primes is zero. Now, in order to obtain a function that behaves more like \(x\) we need to give the primes a sufficient weight. It is the nature of the Prime Number Theorem that the \(n\)th prime is about \(n\log n\). This means that we need to give each prime weight \(\log n\) to obtain a function that behaves like \(x\). This function was first introduced by Pafnuty Chebyshev, is usually called \(\vartheta(x)\), and formally defined as \(\vartheta(x):=\sum\log p\), where the sum runs over all primes not exceeding \(x\). Just for the sake of completeness, I will mention the closely related function \(\psi(x)\) that gives weight \(\log p\) not only to primes, but also to prime powers \(p^n\).

Both functions \(\vartheta(x)\) and \(\psi(x)\) may seem a little artificial at first glance, but they are in fact very natural in the context of counting primes. It is probably best depicted by the fact that the Prime Number Theorem \(\pi(x)\sim x/\log x\) is equivalent to \(\vartheta(x)\sim x\) and \(\psi(x)\sim x\). This relates to my earlier comment that we assign a certain weight to the primes in order to obtain a function with a positive density. Many equations including prime counting functions become more concise by writing them in terms of \(\vartheta(x)\) instead of \(\pi(x)\).

To confuse things even further, we will need yet another prime counting function for our purposes. It is usually denoted \(J(x)\) and counts all the primes below \(x\) plus half the prime squares plus a third of the prime cubes etc. How many numbers below \(x\) are the perfect square of a prime? It may sound tricky to count these, but it’s quite easy if we approach the problem from the other direction: How do we generate all prime squares not exceeding \(x\)? Well, we go through all the primes and take their square. We stop as soon as \(p^2\) exceeds \(x\). In other words, we can generate a prime square for every prime below \(\sqrt{x}\). And here’s our answer! There are \(\pi(\sqrt{x})\) prime squares not exceeding \(x\). The same argument goes for cubes and higher powers. This gives us a neat formula for \(J(x)\):

\[ J(x):=\sum_{n\ge1}\frac{1}{n}\pi(x^{1/n}). \]

It is worth noting that this is actually a finite series. No matter how large you choose \(x\), the value \(x^{1/n}\) will get smaller as the \(n\) in the series increases, and will eventually drop below \(2\). Since there are no primes smaller than \(2\), the value of \(\pi(x^{1/n})\) for that \(n\) and all subsequent ones will be zero, effectively terminating the sum.

There’s another way of expressing \(J(x)\). The same way that \(\pi(x)\) can be expressed as a straightforward “counting sum”

\[ \pi(x)=\sum_{p\le x}1, \]

which literally just means “count \(1\) for each prime”, we can write down the same for \(J(x)\). How exactly do we count here? Well, for any prime \(p\), we count \(1\) for the prime, \(1/2\) for the square \(p^2\), \(1/3\) for the cube \(p^3\), etc. Then we just add up everything:

\[ J(x)=\sum_{n\ge1}\sum_{p^n\le x}\frac{1}{n}. \]

The cool thing is that we can get the value of \(\pi(x)\) back from \(J(x)\) through a technique called Möbius inversion. It is actually not too difficult but slightly out of scope here, so let’s be content for now that we can invert certain sums by means of the so-called Möbius function \(\mu(n)\). This and similar inversion techniques would deserve an article on their own right, but for now without further ado, this is the inverted formula:

\[ \pi(x)=\sum_{n\geq1}\frac{\mu(n)}{n}J(x^{1/n}). \]

You may think: Big whoop! We wrote down a much more complicated function, just to find another complicated expression to get our initial object of study back, but haven’t learnt anything new. The great news is that we can calculate \(J(x)\) to any precision we care with the aid of the \(\zeta\)-function and its zeros.

But that’s the subject of the next article. (Am I getting better at my cliffhangers?)